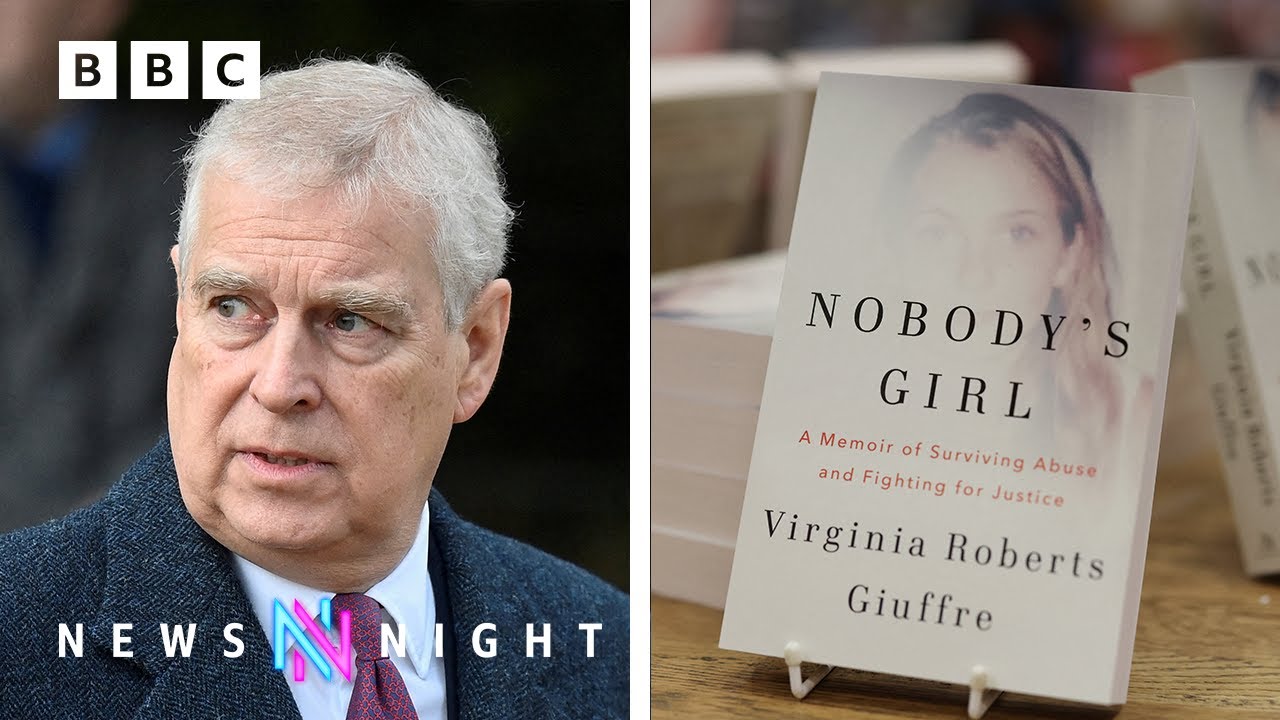

When Virginia Giuffre’s memoir was published posthumously, its pages reopened a story many thought had been told — but not fully heard. Co-written with Amy Wallace, Nobody’s Girl offers a detailed, personal account of trafficking and abuse at the center of the Jeffrey Epstein network, and makes raw, specific allegations about Prince Andrew that the Duke has long denied.

Giuffre’s narrative is not only a catalogue of abuse; it is a chronicle of survival and the fraught path toward speaking out. As Wallace told BBC Newsnight, Giuffre decided to go public after having a daughter — a turning point that made confronting her abusers a moral imperative. “I’m realizing I’m sending her out into the world where she could experience much anything like I had and so I need to do something,” Wallace quotes Giuffre as saying. “At that point she decides I’m going to come forward publicly and try to hold my abusers to account.”

The memoir alleges three encounters with Prince Andrew. The first, Giuffre says, occurred in March 2001 in London when she was 17. She describes being taken shopping by Ghislaine Maxwell to prepare for the meeting, and later being instructed, by Maxwell and Epstein, to “do for him what you do for us.” The third alleged encounter is placed on Epstein’s Little St. James island — a location that has become synonymous with the abuse network — and, according to the memoir, involved Andrew, Epstein and other young girls who arrived from abroad, some reportedly procured by a Paris modeling agent and unable to speak English.

These claims are harrowing in their detail: Giuffre recounts extreme abuse and an incident in which a former minister allegedly raped and choked her to unconsciousness on the island. For safety reasons, she did not name every alleged abuser in the book — a choice Wallace explains as borne of fear: Giuffre worried the minister “would hurt her or kill her.” That fear, she adds, is part of why survivors often keep silent for years.

Amy Wallace does not mince words about Maxwell’s role. She rejects the sanitized label of “receptionist” and calls Maxwell “a master procurer,” placing the mechanism of recruitment and control squarely in Maxwell’s hands. Wallace’s testimony lends force to Giuffre’s aim: this is a deliberate, organized system of exploitation that thrived in the shadows of privilege.

For Prince Andrew, the book compounds years of reputational damage. Though he has repeatedly denied wrongdoing, those denials have not stemmed the public and political consequences. Wallace says Giuffre would see the Duke giving up his Duke of York title as a “victory.” Whether voluntarily relinquished or stripped through legislation under discussion in Parliament, the erosion of Andrew’s public role is now part of the memoir’s aftermath.

The timing of the memoir’s publication — after Giuffre’s death earlier this year — intensifies the emotional stakes. Wallace calls Giuffre a “galvanizer” and a “hero,” emphasizing that the book was written to protect others and to force a reckoning. Giuffre’s choice to go public was shaped by motherhood and by a desire to stop cycles of abuse: “She needed to do something,” Wallace says, “so that anyone who might be sent into the same situation later would not have to live in silence.”

There are broader implications beyond one royal. Giuffre’s account touches on systemic failures: how wealth and status can create impunity, how victims can be silenced by fear, and how institutions — whether legal or social — often struggle to hold powerful people to account. The memoir alleges that Andrew’s legal team engaged in tactics including hiring online operatives to discredit Giuffre and trying to evade legal service at royal estates — a portrayal that feeds a larger narrative about how influence can be used to deflect scrutiny.

Reaction has rippled across the political and social landscape. UK lawmakers are revisiting the mechanisms for rescinding royal titles, and some MPs are pushing for inquiries into how royal residences and resources may have been used. Public pressure is mounting for fuller cooperation with investigators. Wallace urged Andrew to come forward and tell what he knows: “I still deny that I was involved… However I was in these houses and I was on that island and I was on the jet and I saw things,” she said, underscoring that proximity to the events creates an obligation to help unravel the truth.

The memoir also revisits other figures in the Epstein network. Wallace confirms Giuffre met Donald Trump at Mar-a-Lago when she worked there as a “towel girl,” and remembers Trump being “kind” to her in those early days. These recollections do not equate to allegations against every acquaintance, but they expand the web of context in which Epstein’s circle operated — a social and financial ecosystem that allowed predation to persist.

Critics of Giuffre and her account stress the Duke’s denials and point to previous legal settlements as complicating factors. Defenders of Giuffre emphasize the long pattern of testimony from survivors and investigators that aligns with many of the memoir’s claims. The tension between legal outcomes, public opinion and moral accountability is at the heart of the current debate.

What the memoir makes indisputably clear is that Virginia Giuffre chose to tell her story for reasons that went beyond personal closure. Her decision to publish, even as she feared for her safety, was meant to illuminate a system that harmed many and to press for answers that power had too often delayed. Wallace describes Giuffre not as a simple victim, but as a galvanizing force whose words might yet push institutions to act differently.

If nothing else, Nobody’s Girl strengthens the chorus calling for clarity: public figures implicated by association or accusation face renewed scrutiny; legal and parliamentary processes are under pressure to respond; and the public is asked to reckon with the uncomfortable reality that privilege can shield wrongdoing unless exposed and challenged.

Virginia Giuffre’s memoir does not offer tidy closure. It offers pain, memory, and a plea for change. For Prince Andrew, the public erosion of titles and status is, in Wallace’s words, “as it should be” if wrongdoing is borne out. For survivors and advocates, the memoir is another step toward accountability. And for a public that has watched the scandal unfold in fits and starts over the last decade, it is a powerful reminder that silence is often a product of fear — and breaking that silence can be both brave and necessary.

As the nation watches how institutions respond, Giuffre’s final, public act remains clear: she put her story into the world so others might be safer. If the memoir provokes legal heft, political consequence or cultural change, it will have done exactly what she intended — to make sure the powerful are no longer beyond scrutiny.

News

The Border Breakdown: Bill Maher’s ‘Unlocked Gate’ Critique and the Emotional Reckoning of Kamala Harris’s Failed Tenure

The ongoing crisis at the Southern border is not merely a political problem; it is a sprawling humanitarian emergency that…

The Secret Service Showdown: How Donald Trump’s Public Post Ended the Security Nightmare for Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Revealed a Surprising Character

The high-stakes world of American presidential politics is a treacherous landscape, one where the political battlefield often intersects tragically with…

Give Your Money Away, Shorties: Billie Eilish Challenges Billionaires Amidst Government Shutdown and the Great Wealth Transfer

The glittering, insulated world of the ultra-wealthy was abruptly pierced by a jolt of raw, unapologetic accountability. On a recent…

The Odometer of Deception: Jim Carrey’s Devastating Metaphor Exposes the Illusion of ‘Greatness’ and the Destruction of American Institutions

In the fractured, hyper-partisan landscape of contemporary American politics, moments of raw, unfiltered truth often emerge not from the halls…

The Late-Night Rebellion: Why Fallon, Meyers, and a Defiant Stephen Colbert United to Condemn the Suspension of Jimmy Kimmel Live!

The world of late-night television, a realm typically defined by celebrity interviews, viral sketches, and intense network rivalry, was abruptly…

The Anatomy of a Hug: Inside the “Inappropriate” JD Vance and Erica Kirk Interaction That Launched a Viral ‘MAGA Fanfic’ Firestorm

In the digital age, a single photograph can unravel a political narrative, ignite a cultural firestorm, and spawn a thousand…

End of content

No more pages to load