In a staggering reversal of fortunes that has left many studio executives in Hollywood red-faced, the cinematic box office is no longer being sustained by the traditional flow of major American blockbusters. Instead, the lifeline for many theaters, both domestically and globally, is being unexpectedly provided by the rising tide of anime—a genre once dismissed as niche, now hailed as the financial and creative engine “saving the box office.”

This cultural shift highlights a growing, palpable disconnect between what traditional Hollywood is producing and what audiences are actually willing to pay to see. Viewers are overwhelmingly rejecting uninspired mainstream releases in favor of creative, story-driven content, leading to a financial reliance on Japanese animated films that few predicted even a decade ago.

The evidence of anime’s financial dominance is undeniable. Recent box office reports have highlighted the strong performance of titles like Chainsaw Man, which notably “demolished most of the competition” during a recent weekend, pushing mainstream releases out of the top five. While the film didn’t reach the record-shattering heights of previous hits like Demon Slayer, its success underscores a sustained, predictable demand that has permanently altered the theatrical ecosystem.

The financial struggles of traditional Hollywood releases stand in stark contrast to this success. Films like Tron Aries earned less than $5 million that same weekend, managing only $108.4 million globally—a figure significantly lower than even the domestic gross of other struggling major studio properties. The discussion points out the broader financial woes plaguing studios like Disney, where analysts suggest that even “billion-dollar movies” often fail to turn a substantial profit due to exorbitant production and marketing costs. This demonstrates that high gross revenues no longer guarantee profitability, forcing a critical look at the entire studio model.

The influence of anime is no longer viewed as an occasional anomaly or “found money.” Instead, the output from studios and distributors like Crunchyroll is now a regular, expected, and necessary component of the theatrical release schedule. Successful anime are now considered significant box office draws, a dramatic change from the 1990s and early 2000s, when releases like early Dragon Ball movies were largely confined to niche markets.

The desperation within the theater industry is further evidenced by the growing reliance on older, “tried and true” films. The cinematic calendar is now frequently peppered with classic anime theatrical re-releases, signaling that theaters are struggling to fill seats with new Hollywood fare.

The list of films returning to the big screen is a testament to the enduring quality of Japanese animation: Mononoke, Perfect Blue, Akira, Grave of the Fireflies, Paprika, Cowboy Bebop: The Movie, Ninja Scroll, and Metropolis. These films, which hold a cherished place in cinematic history, are proving more reliable attractions than many new, expensive studio releases.

This trend extends to other non-traditional content as well. The hosts point to the unexpected success of low-budget horror movies, such as Weapons and Terrifier, along with the phenomenal, creativity-driven success of Godzilla Minus One. These films were significantly cheaper to produce and were prioritized “about story first,” directly contrasting with the bloated budgets and creatively bankrupt approach often criticized in modern mainstream cinema. The core argument here is that audiences are actively seeking “new things,” “indie stuff,” and “creative stuff” that deliver genuine emotional connection and compelling narratives.

The growing financial success of anime has triggered a major concern among fans and critics: the potential for Hollywood to “westernize and destroy” these valuable intellectual properties (IPs). Hollywood, particularly figures associated with Disney, is criticized as being “masterful at destroying IP,” humorously coining the term “the anus touch”—the idea that “everything you touch will turn to ass.”

The fear is that Hollywood will attempt to infiltrate the highly successful anime industry and strip away the unique cultural and artistic elements that made the properties popular in the first place. Critics predict that “activist parasites” could infiltrate the anime industry, much like the controversies seen in the video game sector, to push diversity agendas and enforce changes that fundamentally alter the character and narrative core of the original work. This is seen as a major threat that could ultimately lead to accusations of “xenophobia” against Japanese-centric stories simply for remaining true to their cultural origins.

The historical context provided reinforces the magnitude of this achievement. The hosts recall a time in the 1990s when the “Japan Animation” section at Blockbuster Video was tiny, holding only a handful of VHS tapes. Anime’s journey from this tiny niche to a mainstream powerhouse, capable of financially stabilizing theatrical releases, is monumental.

The underlying message is a powerful condemnation of Hollywood’s creative laziness and formulaic output. Audiences are no longer content with repetitive sequels and uninspired tentpoles. They are voting with their wallets, clearly “rejecting the Hollywood stuff in favor of pretty much anything else.”

The ultimate hope expressed by the hosts is that Japanese creators will “hold up their own” and maintain their artistic integrity, resisting the enormous financial and cultural pressure from the West to alter their content to fit prevailing Western ideological trends. The future of the theatrical box office, they contend, may well depend on the ability of anime to continue delivering on its promise of story and character connection, thereby paving the way for a new era where content quality, regardless of its origin, dictates success. Anime’s victory at the box office is not just a financial triumph; it’s a creative mandate.

News

The Border Breakdown: Bill Maher’s ‘Unlocked Gate’ Critique and the Emotional Reckoning of Kamala Harris’s Failed Tenure

The ongoing crisis at the Southern border is not merely a political problem; it is a sprawling humanitarian emergency that…

The Secret Service Showdown: How Donald Trump’s Public Post Ended the Security Nightmare for Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Revealed a Surprising Character

The high-stakes world of American presidential politics is a treacherous landscape, one where the political battlefield often intersects tragically with…

Give Your Money Away, Shorties: Billie Eilish Challenges Billionaires Amidst Government Shutdown and the Great Wealth Transfer

The glittering, insulated world of the ultra-wealthy was abruptly pierced by a jolt of raw, unapologetic accountability. On a recent…

The Odometer of Deception: Jim Carrey’s Devastating Metaphor Exposes the Illusion of ‘Greatness’ and the Destruction of American Institutions

In the fractured, hyper-partisan landscape of contemporary American politics, moments of raw, unfiltered truth often emerge not from the halls…

The Late-Night Rebellion: Why Fallon, Meyers, and a Defiant Stephen Colbert United to Condemn the Suspension of Jimmy Kimmel Live!

The world of late-night television, a realm typically defined by celebrity interviews, viral sketches, and intense network rivalry, was abruptly…

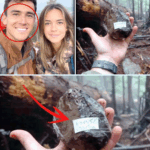

The Anatomy of a Hug: Inside the “Inappropriate” JD Vance and Erica Kirk Interaction That Launched a Viral ‘MAGA Fanfic’ Firestorm

In the digital age, a single photograph can unravel a political narrative, ignite a cultural firestorm, and spawn a thousand…

End of content

No more pages to load