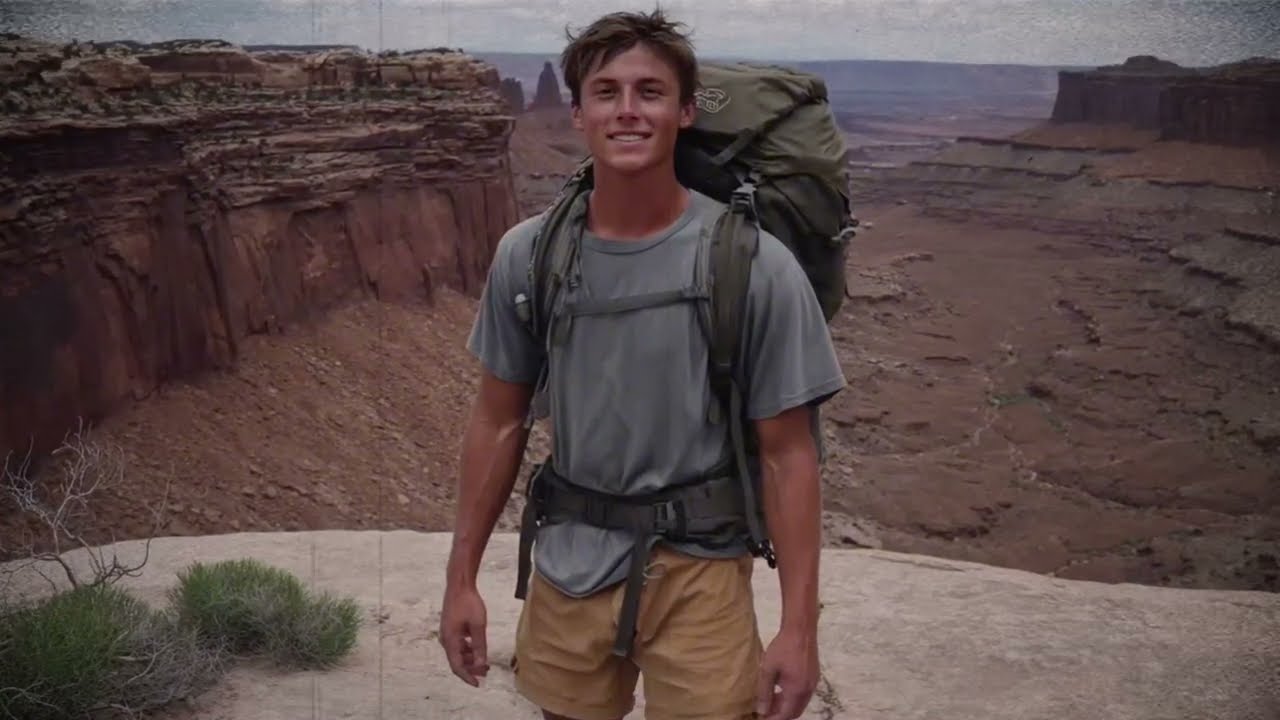

The red rock country of Utah is a paradox of staggering beauty and deadly, unforgiving isolation. The canyons are ancient, silent cathedrals carved by time and water, but they are also labyrinthine traps where one wrong step can lead to an inescapable void. When 34-year-old Joshua “Josh” Vance, an experienced solo backpacker from Denver, failed to emerge from a planned week-long trek through a remote section of Canyonlands National Park, the immense scale of the wilderness instantly became the central focus of a massive, agonizing search. Josh wasn’t careless; he was a meticulous planner, a lover of solitude, and acutely respectful of the desert’s power. Yet, on a clear, warm afternoon in late summer, he simply disappeared.

The red rock country of Utah is a paradox of staggering beauty and deadly, unforgiving isolation. The canyons are ancient, silent cathedrals carved by time and water, but they are also labyrinthine traps where one wrong step can lead to an inescapable void. When 34-year-old Joshua “Josh” Vance, an experienced solo backpacker from Denver, failed to emerge from a planned week-long trek through a remote section of Canyonlands National Park, the immense scale of the wilderness instantly became the central focus of a massive, agonizing search. Josh wasn’t careless; he was a meticulous planner, a lover of solitude, and acutely respectful of the desert’s power. Yet, on a clear, warm afternoon in late summer, he simply disappeared.

Josh’s car was found at the rarely used trailhead leading into the Maze district—a name that perfectly describes the confusing, deadly network of slot canyons and towering mesas. He had filed a detailed permit and route plan, making searchers initially optimistic. However, the Maze is not a place for linear searching. It is a three-dimensional puzzle of cliffs, deep crevices, and hidden pockets that can swallow a person whole, miles from any recognizable path.

The initial days of the search were brutal, relentless, and ultimately fruitless. Park Rangers, aided by specialized tracking teams, K-9 units, and aerial surveillance, covered hundreds of square miles. They found faint footprints leading down a dusty wash, but the soft earth quickly gave way to sandstone and slickrock, which holds no track. The GPS data from his phone was useless, as the deep canyons instantly cut off any satellite signal. The consensus quickly formed: Josh had either taken a catastrophic fall into an unseen crevice or, more likely in that terrain, become hopelessly lost and dehydrated in an unmapped side canyon.

As the weeks bled into a month, the search transitioned into a grim recovery operation. The desert’s intense heat gave way to the sharp chill of autumn nights, further decreasing the already faint hope of finding Josh alive. His parents, who flew in from the Midwest, spent every waking hour coordinating volunteer efforts, desperately appealing to the public for any possible sightings. They knew Josh had carried emergency gear, including flares, a first-aid kit, and enough rations for ten days, but they also knew the canyon system had an infinite capacity to defeat human ingenuity.

The official search was eventually scaled back, a crushing necessity dictated by dwindling resources and the overwhelming complexity of the terrain. The Vance family, like many families of the missing, could not accept the finality of the cold file. They fundraised relentlessly, hiring private search teams composed of seasoned desert experts and local guides, people who understood the canyon’s secrets better than any map.

The official search was eventually scaled back, a crushing necessity dictated by dwindling resources and the overwhelming complexity of the terrain. The Vance family, like many families of the missing, could not accept the finality of the cold file. They fundraised relentlessly, hiring private search teams composed of seasoned desert experts and local guides, people who understood the canyon’s secrets better than any map.

Two more months passed. The desert transitioned into the quiet, frozen stillness of winter, making organized searches virtually impossible. But one guide, a veteran named Silas who had spent forty years exploring the Canyonlands’ hidden corners, held onto a theory. Silas believed Josh, when realizing he was dangerously lost, would have sought the most consistent resource in the desert: shelter from the sun, which often meant a cave or a protective overhang. He focused his winter search efforts on the remote, shadowy, north-facing walls of the deeper canyons, reasoning that these dark spots would provide the clearest contrast against the pale snow and ice.

The area Silas targeted was locally known as the “Whispering Spires,” an exceptionally difficult area requiring rappelling gear and specialized climbing knowledge to access. Three months to the day after Josh vanished, Silas and his partner, braving near-freezing temperatures, descended a sheer cliff face into a tight, unnamed side canyon that ended abruptly in a massive, chaotic jumble of fallen boulders. Tucked beneath the largest boulder, almost completely obscured, was a low, dark opening—a small, natural rock shelter or cave.

The entrance was so small they had to crawl to enter. Inside, the cave opened into a pocket roughly the size of a small tent, protected from the wind and surprisingly dry. The air was still and cold. It was here, in the absolute solitude of the earth, that they found Josh.

He was resting against the far wall, having passed away peacefully. He was still clad in his hiking gear, his head tilted slightly against the cold stone. Beside him lay his pack. The initial wave of professional sorrow gave way to an acute, agonizing curiosity as Silas’s partner shined his headlamp around the small enclosure.

The cave floor was bare sand and rock, but immediately surrounding Josh, fanned out in a nearly perfect, heartbreaking semicircle, were hundreds—perhaps thousands—of burned wooden matches.

The scene was profound, a physical manifestation of a man’s desperate, three-month struggle against total isolation. Josh’s pack, when examined by the Sheriff’s office, contained the usual survival gear, including two full boxes of emergency matches, designed to be waterproof and easy to light. The vast majority of the matches were gone.

The scene was profound, a physical manifestation of a man’s desperate, three-month struggle against total isolation. Josh’s pack, when examined by the Sheriff’s office, contained the usual survival gear, including two full boxes of emergency matches, designed to be waterproof and easy to light. The vast majority of the matches were gone.

Forensic analysis and subsequent psychological profiling suggested a narrative of survival that was both heroic and tragic. Josh had survived for a remarkable amount of time in that cave, sheltered from the elements and likely rationing his water from a small seep found nearby. But the desert’s ultimate weapon is not dehydration or exposure; it is the crushing weight of isolation and the darkness of the mind.

The matches, investigators concluded, were not simply used for warmth or light. They were a timekeeping device. Alone in the absolute void of the cave, without a working clock or calendar, Josh had used the striking of each match to mark the passage of time—a day, a meal, a shift in his mental state. Each tiny flicker of light was a brief defiance of the endless, consuming darkness, a desperate attempt to maintain his sanity and mark the slow march of his existence until rescue could arrive.

The pattern of the matches confirmed the struggle. They were spread out in small clusters, suggesting periods of quiet desperation followed by bursts of frenetic activity. The final cluster, right beside his hand, showed matches struck until the box was empty, suggesting his final hours were spent in a heartbreaking attempt to signal, or perhaps simply to create one last, brief moment of light and purpose before his body gave out.

The medical examiner confirmed that Josh had succumbed to severe dehydration and hypothermia, exacerbated by the long period of extreme rationing. He didn’t die from a sudden fall or a major injury; he died from the relentless, slow siege of the environment, and perhaps, the psychological burden of absolute solitude.

The case of Josh Vance, solved by the smallest, most ephemeral pieces of evidence, became a legend among search and rescue teams. It transformed the simple matchstick from a tool of fire into a symbol of human resilience and ultimate vulnerability. The hundreds of burned cerillas were not a sign of failure, but a testament to a three-month will to live—a grim, beautiful record of a man’s final days, written in smoke and sulfur on the floor of a forgotten cave.

The case of Josh Vance, solved by the smallest, most ephemeral pieces of evidence, became a legend among search and rescue teams. It transformed the simple matchstick from a tool of fire into a symbol of human resilience and ultimate vulnerability. The hundreds of burned cerillas were not a sign of failure, but a testament to a three-month will to live—a grim, beautiful record of a man’s final days, written in smoke and sulfur on the floor of a forgotten cave.

For Josh’s family, the discovery, though heartbreaking, brought a profound, desolate peace. They understood that in his final moments, Josh was not resigned to fate; he was fighting, marking his time, illuminating his own darkness, match by match, until the last one burned out. The cave in the Whispering Spires became a sacred space, not just a tomb, but a chronicle of a lonely, courageous last stand against the wild, silent power of the Utah canyonlands.

News

The Mountain Whisper: Six Years After a Couple Vanished in Colorado, a Fallen Pine Tree Revealed a Single, Silent Stone

The Rocky Mountains of Colorado possess a severe, breathtaking grandeur, offering both profound beauty and relentless danger. For those who…

The Ghost Pacer: How a Hiker Vanished in the Redwoods, Only for Her Fitness Tracker to Start Counting Steps Nine Months Later

The Redwood National Park is a cathedral of nature, a place where the trees stand like silent, ancient guardians, scraping…

The Haunting of the Sisters: How a Lone Discovery in an Idaho Forest Three Years Later Revealed a Silent Terror

The woods, especially the vast, ancient forests of Idaho, hold a unique kind of stillness. It’s a quiet that can…

The Locker Room Ghost: A Demolition Crew’s Routine Job Unlocks the Thirteen-Year Mystery of a Vanished Teen

The year was 2011, and the world seemed full of possibility for sixteen-year-old Ethan Miller. A bright, quiet student with…

The Ghost Kitchen: How a Missing Food Truck and a Routine Drone Flight Unlocked a Seven-Year-Old Mystery

Food trucks represent a certain kind of American dream: mobile, entrepreneurial, and fueled by passion. For Maria and Tomas Rodriguez,…

The Ghost Road Trip: Seven Years After a Couple Vanished, a Stranger’s Discovery Unlocked a Tragic Mystery

The open road holds the promise of freedom, adventure, and new beginnings. When Sarah Jenkins and David Chen decided to…

End of content

No more pages to load